Hello everyone Adam here! Until now we have been talking about festivals and their interactions with Hellenistic kingdoms, but what about the smaller festivals that impact regions? In this post, I am going to focus on a much smaller festival, without sporting events, that helped to shape the identity of people in the Greek region of Thessaly during the Hellenistic period. This helps us understand how groups of people identified within a smaller area and how people connected closely with their surroundings.

This particular festival was held in the Eastern Thessalian perioikos of Magnesia on Mount Pelion, located next to the Aegean Sea. The name of the festival is unclear, but it is possible it was called the “Chironidai festival”, as the chironidai were the descendants of Chiron who was sacred to the area around Mount Pelion. It was on Mount Pelion that Chiron is said to have trained many heroes such as Achilles so Chiron was of special mythological importance to the region and it is suggested many people worshipped him.

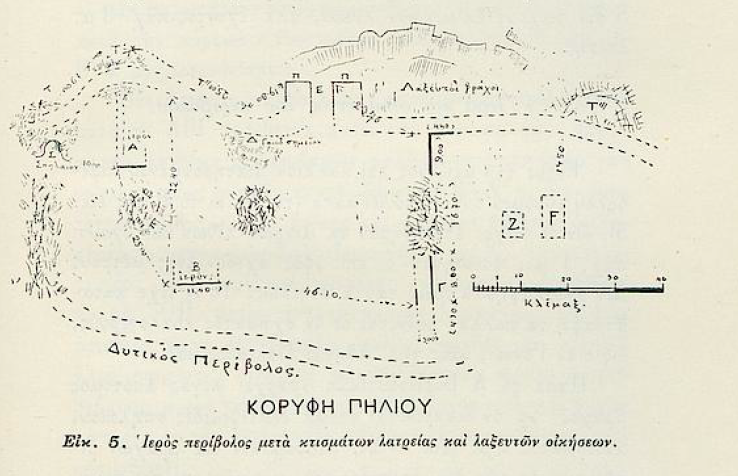

A sanctuary of Zeus Akraios and a cave of Chiron was partially excavated by Apostolos Arvanitopoulos in 1911 on Mount Pelion. Arvanitopoulos mapped out a plan of the site that can be seen below.

So, what is known about the festival? What we know about this festival comes from a 3rd c. BC literary text of Herakleides Kritikos (originally attributed to Dikaiarchos):

“On the peak of the mountain’s topthere is the cave called the Chironion and a shrine to Zeus Aktaios. At the rising of the Dog Star, the time of greatest heat, the most distinguished of the citizens (of Demetrias) and in the prime of their lives ascend, having been chosen in the presence of the priest, clad in thick new fleeces – so cold is it on the mountain.” (FHG II, fr. 60. 8, pg. 262 = BNJ 369A F2.8)

Interestingly, in this passage, Herakleides refers to the shrine of Zeus Aktaios instead of Akraios. This is generally thought to be a mistake as many inscriptions from the area mention a Zeus Akraios but a Zeus Aktaios is never mentioned.

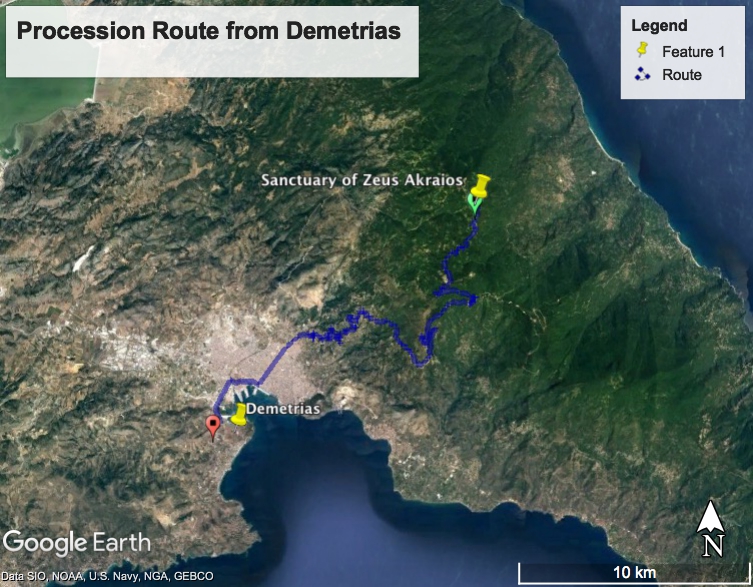

As there are no other sanctuaries on Pelion’s other peaks, we know that this is referring to the site excavated by Arvanitopoulos, and we know the procession is started at the newly founded city of Demetrias (founded in 294/3 BC by Demetrios Poliorketes). Although material evidence from the site indicates people travelled to the site from around Magnesia from as early as the 5th c. BC, this is the first written evidence that a formal procession occurred every year.

In previous blog posts we have talked about agonistic festivals (festivals with a sporting aspect), but many festivals that happened contained just a religious aspect and that is what we are seeing here. Annually youths dressed up in ram-skins and processed to a sanctuary that was around 30 km away on the top of a mountain. As this sanctuary was located at the top of Mount Pelion, it was an extra-urban sanctuary, meaning it was located outside of a city, and this procession to the sanctuary was a way for sacred space to be crafted as the sanctuary was a symbolic boundary of Magnesian territory. We can see on the map below a possible route to the sanctuary, though the precise route taken is unknown.

Regional festivals such as this one had a different purpose than the large Pan-Hellenic festivals like the Great Panathenaia at Athens. They were a way for people within a defined area to connect with one another and they aided in formation of a cohesive identity where people in the area all knew this procession was happening and why they were performing the ritual. The landscape of Mount Pelion was anchored in various myths and Chiron was a central figure. This small festival allowed for people to not only connect with each other, but was a way for people to connect with the landscape around them.

Of course, the fragmentary evidence we have with regard to this festival leads to lots of questions, which I hope to develop further in my research!

Adam

Further Reading

Aston, E. 2006. “The Absence of Chiron.” The Classical Quarterly 56(2): 349-362.

—. 2009. “Thetis and Cheiron in Thessaly.” Kernos 22: 83-107.

Gorrini, M.E. 2006. “Healing Heroes in Thessaly: Chiron the Centaur.” AEΘΣΕ 1: 297-309.

Kravaritou, S. 2018. “Cults and Rites of Passage in Ancient Thessaly.” In Βορειοελλαδικά: Tales from the lands of the ethne. Essays in honour of Miltiades B. Hatzopoulos. Eds. M. Kalaitzi, P. Paschidis, C. Antonetti, and A.-M. Guimier-Sorbets. Athens: 377-396.