Hello again! So far we have looked at festivals founded or sponsored by rulers, but that was not the limit of Hellenistic royal involvement with the agonistic world. Kings, queens and other members of the dynasties frequently entered themselves as competitors in major sporting festivals, continuing a practice of the Makedonian monarchy that dates back to at least the reign of Alexander I (c.498-454 BC).

By the 4th century royalty seem to have restricted themselves to the entering of race-horses and chariot teams. Usually in ancient Greek equestrian events the competitors did not ride or drive their horses in person, with this task being left to slaves. Kings were thus spared the indignity of defeat at the hands of career athletes in the prime of their youth, and could use their great wealth to rear and purchase the very best horses. (Also notable is that this approach allowed royal women to compete in an almost entirely male-dominated setting.) The exemplar of this strategy was Philip II, who garnered much prestige and goodwill among the Greek cities with his three victories at the Olympics.

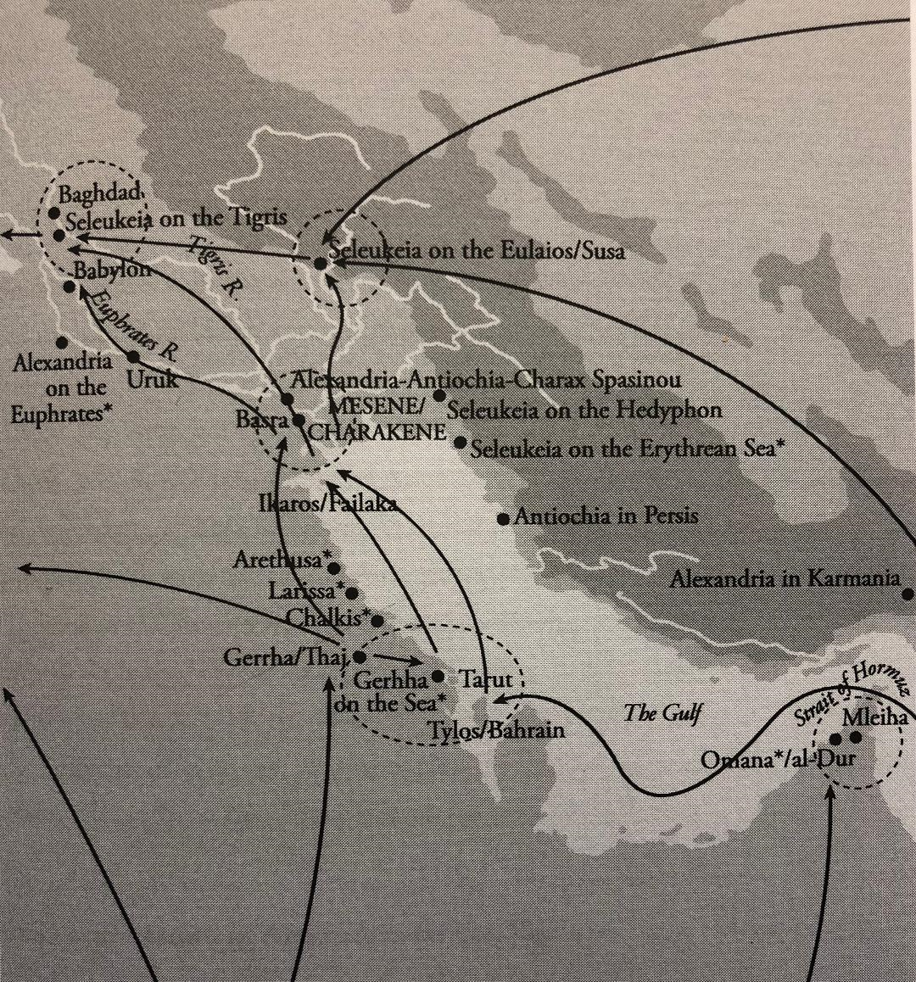

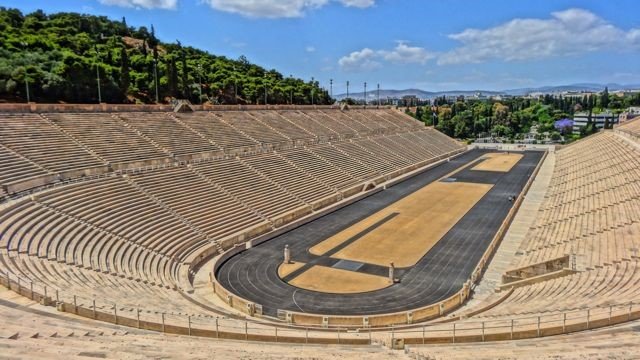

Royal competitors are not always easy to discern in the historical record, but a number of (more or less fragmentary) victor lists from the 2nd century BC give insight into participation in one major festival – the Athenian Panathenaia. This was the largest agonistic festival held at Athens and, while the contests were not part of the periodos of traditional “Panhellenic” games, Athens’ cultural cachet made put them on a similar level to the Olympics and the Pythia. The penteteric* Great Panathenaia thus attracted competitors from the length and breadth of the Greek world, with athletes from as far afield as Italy and Mesopotamia. Several of these competitors were royal, as laid out here:

Royal Panathenaic Victors

182 BC: Ptolemy V – Victor in a four-horse chariot race (Citizens’)

“the son of Ptolemy, the Makedonian” – Ptolemy V again? – Victor in an unknown Panhellenic event

178 BC: Eumenes II – Victor in a four-horse chariot race (Panhellenic)

Attalos (brother of Eumenes) – Victor in a four-horse chariot race (Panhellenic)

Philetairos (brother of Eumenes) – Victor in a horse race (Panhellenic)

Athenaios (brother of Eumenes) – Victor in a two-horse chariot race (Panhellenic)

170 BC: Attalos (brother of Eumenes) – Victor in a two-horse chariot race (Citizens’)

162 BC: Ptolemy VI – Victor in a two-horse chariot race (Citizens’)

Kleopatra (sister and wife of Ptolemy VI) – Victor in a horse race (Citizens’)

Eumenes II – Victor in a four-horse war-chariot race (Citizens’)

158 BC: Mastanabal, son of the Numidian king Massinissa – Victor in a horse race (Panhellenic)

Ptolemy VI – Victor in a two-horse chariot race (Panhellenic)

150 or 146 BC (date uncertain): Alexander Balas (a claimant to the Seleukid diadem) – Victor in a horse race (Panhellenic) and one unknown event

Immediately striking is the variety of royal competitors here – Ptolemies, Attalids, a Seleukid and even a Numidian. A reasonable conclusion to draw would be that competing in the Panathenaia was a strategy of general interest to Hellenistic monarchs, rather than one useful to a particular dynasty. This makes sense, given the number and diversity of participants at the Panathenaia – Athens made a good stage for displays of wealth and power by any ruler around the Mediterranean. We might also infer that these competitors were emulating each other. Once it had been established that winning victories at the Panathenaia brought a dynasty political benefits, other rulers were motivated to contest that victorious position. Particularly important here are the Attalids and Mastanabal, representatives of new powers in the Hellenistic world seeking to show themselves equal to the more established dynasties.

The second feature of this participation that I want to point to is that the class of events entered is also varied. The Great Panathenaia comprised “Panhellenic” contests open to all, and contests restricted to Athenian citizens. During the 3rd century BC, however, the Ptolemaic and Attalid royal families had acquired honorary Athenian citizenship, allowing them to participate in the latter class of races. These two dynasties appear to have switched between the classes in this period, winning victories in both, but why? The open races, taking place in the primary stadium, would have had a larger, more geographically varied audience, and were probably considered more prestigious due to the larger pool of competitors. Yet by competing as citizens these dynasties could demonstrate their special connection to Athens, enhancing the city’s prestige and reaffirming their diplomatic commitment to its welfare. For these dynasties the Panathenaia served both as a means to reach out to the Greek world as a whole, and as a specific connection to a key city in which they desired to promote their influence.

This list raises more questions, of course, and in the next post we will take a look at its most surprising – indeed, unlikely – aspect, the quadruple Attalid victory of 178 BC.

Tom

*Taking place every five years as the ancient Greeks counted: every four years by our reckoning. The Panathenaia was an annual festival, but only every four years (the Greater Panathenaia) were contests opened to foreigners.

Further Reading

Habicht, Christian, “Athens and the Attalids in the Second Century BC”, Hesperia 59 (1990), 561-577.

— “Athens and the Ptolemies”, Classical Antiquity 11.1 (1992), 68-90.

Shear, Julia, “Royal Athenians: The Ptolemies and Attalids at the Panathenaia”, in Olgia Palagia and Alkestis Spetsieri-Choremi (eds.) The Panathenaic Games (Oxbow, 2015), 135-145.