Hello! We’ve already seen that early Hellenistic rulers were willing to spend quite a bit of money and effort on gathering athletes, musicians and other competitors for festivals. At first these were one-off events, separate from the regular circuit of major games which had existed for centuries before Alexander. Yet from about 280 BC that changed – kings started to manage their own regular festivals, creating permanent ties to the Greek civic world in the process. The methods which they used to found and promote these festivals would in time be picked up by the cities themselves and then by the Romans, and some of these newly-founded competitions would come to rival the very oldest games in Greece. But the trend began with a single city, poised between the Mediterranean and the Middle East, one that exemplified all that was new about the Hellenistic era – Alexandria.

The city was founded as a port on the western edge of the Nile delta in 333/2, upon the Makedonian conquest of Egypt. In fact, Alexander founded more than forty different Alexandrias in his career, but “Alexandria by Egypt” grew to be the largest, mainly due to its position as a gateway to wealthy Egypt from the Mediterranean. After Alexander’s death his general Ptolemy made it the capital of a new kingdom, using the enormous fertility of the Nile as a basis for one of the most powerful states in the new Hellenistic political system. By the time of Ptolemy’s death in 283, Alexandria was a major commercial and political centre, and almost unique in Egypt as one of only three cities with Greek civic institutions.

It was thus the natural place for the new king, Ptolemy II, to hold memorials for his late father. In 279, on the fourth anniversary of his father’s death, Ptolemy II established a new, quadrennial festival to be held near Alexandria, called the Ptolemaia. This was swiftly associated with a second, similar set of games, the Theadelpheia, held in honour of Ptolemy II and his new wife (and sister) Arsinoe. A third festival, the Basileia, was dedicated to Royal Zeus, patron of the ruling dynasty. This complex of festivals was an unprecedented creation for a king, and must have entailed considerable expense. Yet Ptolemy II thought it worthwhile not merely to create the new contests but to pursue a vigorous diplomatic campaign to encourage attendance by competitors from across the Greek world.

This strategy is familiar from the later efforts of the Attalid king Eumenes II in promoting his own festivals – indeed, the Ptolemies set the standard for the marketing of royal games. Central to their approach was a request that other cities recognise the new contests as “isolympic” – equal to the Olympics and the Pythia, the most prestigious competitions in Greece. Not only would this raise the profile of the Alexandrian festivals, but crucially it meant that victors at Alexandria would receive the same valuable prizes and public honours in their native cities as would Olympic winners. This recognition (and it was eventually obtained from most, if not all, Greek cities) was thus key to attracting skilled competitors to festivals which had not even existed, let alone been culturally significant, only a few years before.

How successful was Ptolemy? Several records survive of men travelling to Alexandria to compete in the new games, but the quality of talent seems to have been mixed. One tragic actor from the Peloponnese won the boxing contest at the Ptolemaia, which certainly doesn’t suggest a surplus of elite athletes. On the other hand, an extremely successful lyrist who may have been the famous Nikokles of Taras competed at the Basileia, and an Olympic victor won a chariot-race at the Theadelpheia. Perhaps the amateur boxer was the exception rather than the rule, and in general the new festivals did see participation from the highest tier of Greek competitive culture. Statistical analysis of competitors travelling to and from Greek festival sites also suggests that Alexandria became an important node in the wider network of festivals during the third century.

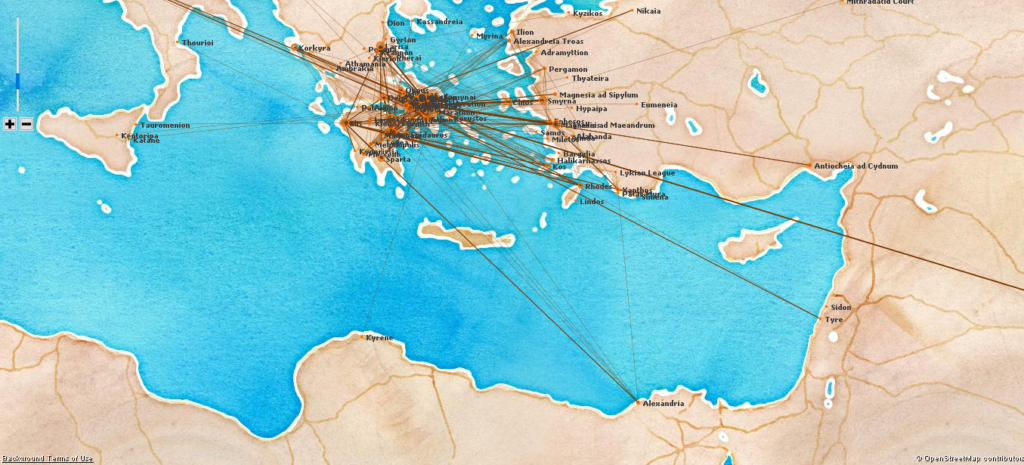

These maps of the dense network of connections between sporting festivals, formed by travelling competitors, show the development of Egypt as a festival centre over time. From humble beginnings at the start of the period, Egypt became a frequent destination for competitors in the 3rd century, only to fall from significance as royal resources declined. (Note that the Ptolemaic court and royal family are separated out from other athletes in these maps, but would in fact have resided in Alexandria.)

Yet competitors are only part of the picture. Another frequent sight at Greek festivals were theōroi, sacred envoys sent to participate in rituals and sacrifices by foreign cities. Ptolemy II and his successors actively encouraged these religious missions, asking all cities which recognised their festivals to send envoys not only when announcing their participation, but to every instance of the games. The Ptolemaia and Theadelpheia fell close together in the calendar, so cities seem to have sent theōroi to sacrifice at both together.

This practice was useful for both the kings and the cities. In this period the Ptolemies controlled a network of naval bases spanning the eastern Mediterranean, and held authority over a large number of coastal cities. Yet these cities had no regular means to communicate with their royal overlords. The sending of theōroi to Alexandria every four years created a predictable diplomatic framework for the negotiation of responsibilities and privileges with the royal court – we know that theōroi were given royal audiences after the festivals and were often in communication with other important court figures. From the Ptolemaic viewpoint, these visits were opportunities to forge relationships with civic politicians and to impress upon them the might and majesty of the kingdom, using the monumental architecture of the capital, grand processions of soldiers and exotic goods, and, of course, the games themselves.

The Alexandrian festivals were thus closely linked to royal strategic interests in the Mediterranean. As Ptolemaic power declined in the second century and royal forces were gradually expelled or withdrawn from their fortresses in the Aegean, so too did the need to engage closely with Greek civic networks. At the same time, growing strains on the royal treasury lessened the appeal of costly festivals. It is not clear whether any of the major contests were ever formally abolished, but after the middle of the second century Alexandria no longer appears as a centre of sporting culture. Only in the Roman period would the city’s fortunes and festivals be revived.

And yet there is still much more to learn from the great Ptolemaic festivals! This entry has looked at them as vehicles for engagement with Greece, but future posts will discuss their impact on sport and competition in Egypt, both in the court and in the countryside. Even more important was the precedent set by the Ptolemaia as the first “isolympic” festival. We will see that this claim, and its eventual acceptance by the Greeks, would transform the Mediterranean festival system forever.

Tom